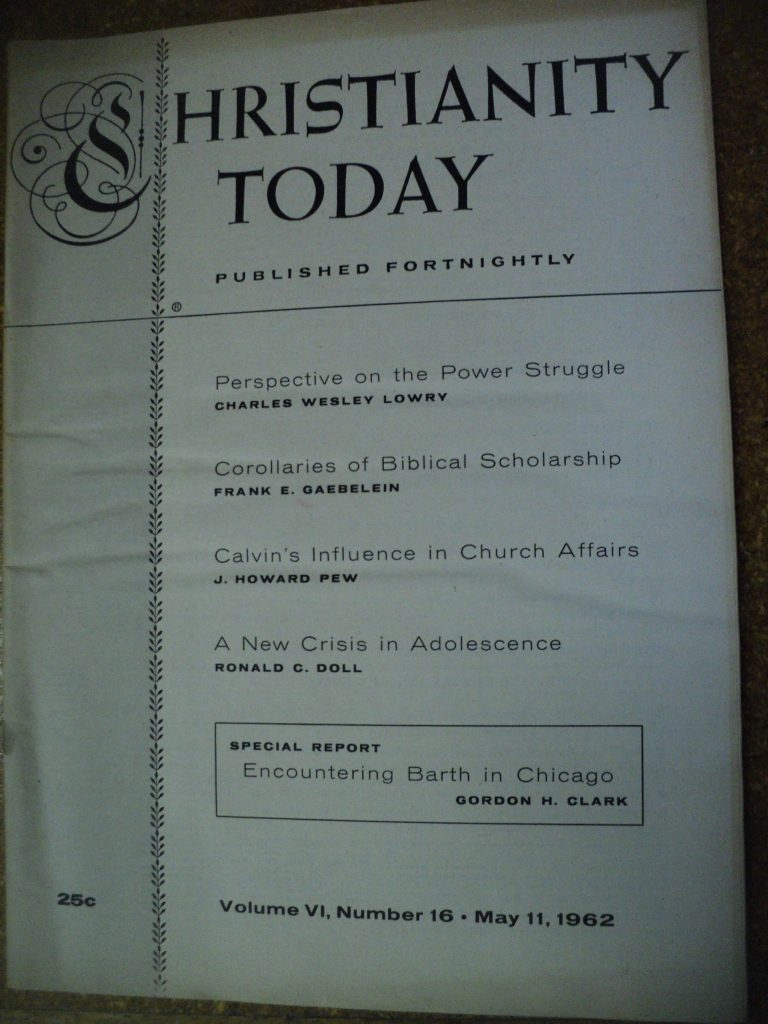

[1962. Special Report: Encountering Barth in Chicago, Christianity Today, May 11, 1962, 35-36.]

Special Report: Encountering Barth in Chicago

The following is a report on the lectures delivered by Professor Karl Barth at the University of Chicago, April 23-27. Barth spoke to overflow audiences of more than 2,000 at each of seven sessions held in Rockefeller Chapel. This report has been prepared expressly for CHRISTIANITY TODAY by Dr. Gordon H. Clark, professor of philosophy as Butler University.

To judge Barth fairly one must ask: What is this distinguished theologian trying to do? During the panel discussion, in answering a question from Professor Schubert M. Ogden of Southern Methodist University, Barth said: “In no sense is theology dependent on philosophy; one of my primary intentions has always been to declare the independence of theology from philosophy, including religion.”

As in his Church Dogmatics Barth reiterated his opposition to a nonhistorical religion of general principles, principles discovered by ordinary human capacity as exemplified in anthropology, sociology, politics, or any other science. Theology is sui generis. The reason is that God is not some Hegelian Absolute to be discovered and manipulated by man. God is the living and free person who has acted and spoken in history. Therefore the place and starting point of theology is the Word of God. “The Word of God spoke, speaks, and will speak again.”

Theology is a response to the Word of God. If it should try to justify itself, if it should try to reserve for itself a place among the sciences, if it should explain or excuse itself, it would destroy its whole significance. Before a man con respond, he must be summoned by the creative Word. Otherwise there is no evangelical theology at all.

These sentiments give content to Barth’s aim to free theology from all science and philosophy. For this reason it seems most just to evaluate Barth’s performance as an attempt to oppose the liberalism and modernism of the last hundred years. He is speaking against Schleiermacher, Ritschl, Harnack, Herrmann, and perhaps also against Bultmann.

Thus can be understood the special place Barth assigns to the history of Israel. It is there, and not in China or elsewhere, that God has spoken. When Professor Edward J. Carnell of Fuller Theological Seminary asked if God could be encountered in reading Confucius, as some Chinese might claim, or in Mozart, whom Barth loves, Barth replied in effect that whatever might be encountered in other sacred writings, it is not the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Barth thus stresses the history of Israel as no modernist ever can. Salvation is of the Jews, and the culmination of their history is Jesus Christ and the empty tomb. In opposition to the liberals Barth insists that the apostles did not preach “the historical Jesus” (of Renan or Harnack) nor did they preach “the divine Christ” (Bultmann), but rather the one concrete Jesus Christ our Lord.

In our preaching today we are dependent on the apostles. Theology knows the Word only second hand; it is not on the same level with the apostles. We today may know more science than they knew, but we know less about the Word of God than they knew. The modern theologian must not sit over them and correct their notes as a schoolmaster corrects the essays of his students. No! The apostles must look over our shoulders and correct our essays!

Obviously this is all in opposition to the History-of-Religion school, and it ill accords with proposals to merge all religions into one world-religion. This latter is based on religious experience, on philosophy, on human capacities. Barth wishes to respond to the Word of God.

The next question is whether Barth can press home his attack on modernism. Can he make good in constructive theological detail?

Father Bernard Cooke, S.J., of Marquette University, asked Barth if knowledge of God arrived at in faith could be integrated with knowledge about God attained in natural theology. Barth, of course, allows no place for natural theology; but his answer to this question was given in the form of a dilemma. If these two knowledges are not identical, they cannot be integrated; but, continued Barth, if they are identical, then the Bible is wrong when it says that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is not the God of philosophy. “The God of philosophy is always an idol,” and then in the manner of Billy Graham, Barth added, “The Bible says so!”

But difficulties arise the more specific the questions become. Ogden, Jakob J. Petuchowski, Hebrew Union College, and Carnell agreed essentially on one question. The Jewish rabbi put it in a slightly different form. He wished to know why one might not select and interpret parts of the Old Testament and even parts of the New Testament without being forced to a central Christology. From a Christian point of view, and especially from an evangelical point of view, Carnell’s formulation is more familiar. “How does Dr. Barth,” asks Carnell, “harmonize his appeal to Scripture as the objective Word of God with his admission that Scripture is sullied by errors, theological as well as historical or factual.”

Carnell confessed parenthetically that “this is a problem for me, too.”

This seems to be a most important question. Can a theology claim to be a biblical theology and reject parts of the Bible as theological and historical errors? Can Barth insist on the independence of theology and then in some way or other select one verse and reject another? Does not such selection require a principle or criterion different from the Bible? Must not a theologian who denies verbal inspiration and Biblical inerrancy use of necessity some philosophic or scientific test of how much and what part of the Bible he will accept?

Barth’s answer does not seem to meet the question. He asserted that the Bible is a fitting instrument to point men to God, who alone is infallible. The Bible is a human document and not sinless as Christ was. Then a large part of the overflow audience—possibly 500 were standing in the aisles or sitting on the stone floor—applauded Barth’s assertion that there are “contradictions and errors” in the Bible. After and possibly because of this expression of hostility, Carnell professed to be satisfied and did not press the matter of a nonbiblical criterion by which to judge what is a theological error in the Bible.

In answer to Rabbi Petuchowski’s question concerning the state of Israel, Barth said that modern Israel is a new sign of the electing grace and faithfulness of God. Especially after the horrors of Hitler, the reappearance of Zion as a state is a miracle. He further observed that the Jews have always owed their existence to God alone, not to their own power. Now today, wedged among the Arab nations and caught in an East-West struggle, God alone will preserve Israel.

A less pertinent not was introduced into the panel discussion by lawyer Frank W. Stringfellow. He requested Barth to comment on his view that “in the United States the many and divided churches lives in a society which constitutionally professes the freedom of public worship … It increasingly appears, however, that the use of that freedom—the only use that is socially approved, at least— is confined to either the mere formalities of religious observance … or to the use of religion to rationalize or serve the national self-interest …”

In explaining his written question, Stringfellow referred to the National Council of Churches’ report on Red China a few years ago. Using the dodge that this was a “study” and not a “official position” of the National Council, Stringfellow seemed to believe that the wide-spread reaction against this pro-Red document on the part of many individual Christians throughout the nation was an infringement on the church’s liberty. In the United States, he claimed, the church is “stifled.” He went on to say that the large loss of income that resulted from the publicity on the Red China issue has made the National Council very careful in making any statement since that time.

Continuing further with Stringfellow’s concern in politics, Barth remarked that Romans 13 is a “disturbing chapter” and played a great role in the submission of the German church to the political leaders. Mere submission, however, is not enough. The verses tell us to place ourselves in a political order; we are commanded to pray for our rulers; this means we are responsible for them. Therefore the Christian must take part in politics and not retire to the position of a spectator.

Nevertheless, in identifying the evil principalities and powers which bedevil the Christian, Barth puts anti-communism in the same class with communism. He also spoke of the evil power of sport, fashion, tradition of all kinds, religion, the unconscious, and reason as well. Sinful man, separated from God, makes these things his rulers; he becomes their servant. Needed is a new heaven and a new earth with a bodily resurrection at Christ’s second coming.

On his last day in Chicago, there was a university convocation where Professor Barth was awarded an honorary degree. Barth again declared in his final lecture, delivered at the convocation, that evangelical theology is without presuppositions. Its statements “could not be derived from any points outside of the sphere of reality and truth which they themselves signify. They had no premises in any results of a general science … and they likewise had no background in any philosophical foundations.”

Most of the last lecture, however, dealt with the Spirit. In various ways Barth insisted that the Spirit blows where he wills; that this is a matter of free grace; and that the Spirit gives himself undeservedly and incalculably.”

It is somewhat of a milestone in the history of American theology that the University of Chicago, so thoroughly liberal in the early part of the century, should now in the sixties award a degree to a man with this much of a biblical message. Doubtless the impact of Barth’s visit will be evident here for the next decade at least.

Barth’s Itinerary

Following his Chicago lectures, Professor Karl Barth was scheduled to proceed to the campus of Princeton Theological Seminary and render what essentially amounted to a repeat performance.

The Princeton series was slated to be part of the seminary’s sesquicentennial celebration.

San Francisco Theological Seminary at San Anselmo, California, announced that “after being importuned” by President Theodore A. Gill, Barth consented to speak to the theological community there on May 16.

Other scheduled stops on the cross-country circuit included Gettysburg battlefields (Barth is an amateur expert on the Civil War) and Washington, where a private dinner meeting was being arranged in his honor.

This is the first time that the 75-year-old Barth has ever visited the United States. It comes upon his retirement from a professorship at the University of Basel, Switzerland.

Barth’s 46-year-old son Markus is a New Testament scholar at the University of Chicago. Another son, Christoph, 44, teaches Old Testament at the University of Djakarta.